NO FOOT, NO DOG

LET’S TALK ABOUT STRUCTURE

with Stephanie Seabrook Hedgepath

The old adage, “No Hoof, No Horse,” common in North America in the 18th century, speaks to how important the feet are to an animal. A lame horse is useless to its owner. The same principle can be applied to the dog “No Foot, No Dog.”

I first heard the phrase used to describe a dog when judging an ARBA show in the late 1990s. A fellow judge (a hound man), whom I greatly admired, chastised me for using a hound with bad feet in the Group. This led to a great discussion and the beginning of a long friendship.

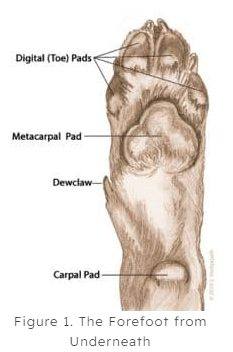

The anatomy of the canine foot comprises the toenails (claws), toes, toe (digital) pads, metacarpal pads, the dewclaw, and the carpal pad. (See Figure 1.) The canine foot has four toes, which are functional and contain three bones to form each toe. A fifth toe, called the “dewclaw”, when not removed, differs from the other four in that it only contains two bones. The feet serve as a base of support for the dog. They serve as a cushion to absorb shock, provide traction to start motion and act as a brake to stop.

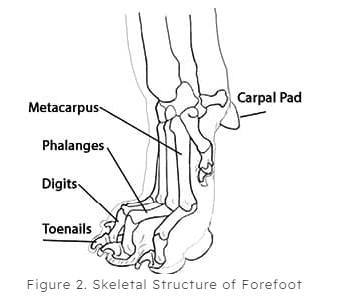

We will start with the toenails or claws at the end of each toe. (See Figure 2.) Composed of keratin, the nails enable the dog to grip the ground and scratch (both the ground and themselves) and help maintain a grip on something they are chewing. The average dog has four functional toes (digits) and may be born with a fifth toe called the dewclaw, located on the front leg’s inner side of the pastern. The dewclaw is considered to have lost most or all of its original function. Dewclaws may also be found on the rear legs. Several breeds require dewclaws on some or all of the legs. On the average dog, however, they are usually removed, especially if they have no contact with the ground.

Each of the toes is supported by a pad composed of thick layers of fat and connective tissue covered with several layers of skin, forming thick, horny skin. This thick skin allows the dog to comfortably work over many types of terrain, from abrasive to slick and slippery. It also varies greatly in fluctuating temperatures. (See Figures 1 & 2.) the pads serve as a weight-bearing, shock-absorbing cushion and aid in traction.

Next comes the metacarpal bones in the front feet, commonly referred to as the pastern. These bones join the pastern joint (carpus joint) with the toes (digits) of the dog. There are four metacarpal bones (five if the dewclaw is not removed), each leading to one of the toes. Of the four, the outer bones (leading to the two outside toes) are shorter than the inner ones (leading to the two center toes). These metacarpal bones relate to the palm of the human hand—between the wrist and the fingers. The dog actually walks only on the toes/digits of its foot. (See Figure 2.) The carpal pads are found on the front feet, farther up the foot, near the wrist or pastern joint. (See Figures 1 & 2.) They are of the same structure as the pads under the toes. The carpal pad plays on steep or slippery surfaces by helping the dog retain its balance. It is also sometimes referred to as the “stopper pad,” working as a brake. This pad also supports the crouching/crawling dog (think Border Collie approaching livestock) as it moves over rough terrain.

The metacarpal pads on the front feet (metatarsal on the rear) are the largest pads on the foot and are located behind the pads of the toes. As with the toe pads, the metacarpal/metatarsal pads provide shock absorption and traction. The metatarsus of the rear is similar to the metacarpus of the front, except that it is longer. (See Figure 1.)

As we move from the toes to the foreleg, the carpal bones form the pastern joint (wrist). The pastern joint is a compound joint formed by articulating the seven carpal bones (stacked in two rows), with the radius and ulna bones of the foreleg on the upper side of the pastern and the metacarpal bones on the lower side. These seven bones form a compound joint that allows for great mobility and has a significant shock-absorbing capacity. This joint allows for the slope of the pastern and provides cushioning for the striking foot. The short bones of the carpus serve to diffuse concussion in the limbs as the bones experience pounding force when a dog runs or lands from a jump. (See Figure 2.) The tarsus, or hock joint on the rear legs, is similar to the pastern on the forelegs as it consists of seven bones arranged in two rows (three on top to articulate with the fibula and tibia bones and four distal that articulate with the metatarsals of the rear foot).

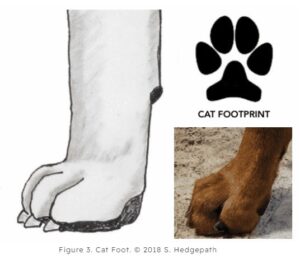

Foot conformation is directly related to the task the breed was developed to accomplish. A Cat Foot is compact, small, and round in shape. It is built for stability, endurance, and bearing great weight. The compact foot is easily picked up during forward movement, allowing a dog to conserve energy. The cat foot works well for dogs that have to move over uneven ground. (See Figure 3.) not surprisingly, it is found on most large Working breeds like the Doberman Pinscher and the Newfoundland.

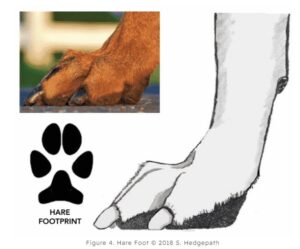

The Hare Foot has two elongated middle toes and is formed for speed, quick direction changes, and fast movement from a standstill. The longer hare foot gives the foot a better grip on the ground when running straight ahead. (See figure 4.) Dog breeds with hare feet include the Whippet and the Greyhound.

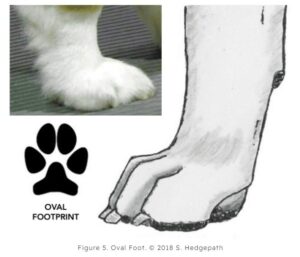

Dogs with oval feet have slightly longer middle toes (shorter than the hare foot and longer than the cat foot) and are for the dog that must be able to endure but also needs the added speed and jumping ability associated with the hare foot. (See Figure 5.) the oval foot is found in breeds as diverse as the Pembroke Welsh Corgi, Basenji, Pointer, Chinook, and Toy Fox Terrier.

Dogs with webbed feet increase the surface area of the foot while providing better movement through water, mud or snow. In breeds such as the Chesapeake Bay Retriever and the Otterhound, the Portuguese Water Dog and the Newfoundland, the webbed foot also serves somewhat as a paddle when swimming. A few breeds even call for “snowshoe” feet to help the dog traverse more easily on snow and ice. The Alaskan Malamute and the Tibetan Terrier ask for snowshoe feet.

Two types of feet considered faulty are flat and splayed feet. The flat foot is usually accompanied by a dog “down in pastern” due to a laxity of the foot’s tendons and carpal joint. (See Figure 6.) A splayed foot is weak, and the toes are spread apart, especially when in motion. (See Figure 7.)

Foot shape can be affected by heredity, lack of exercise during critical periods of development, and improper ground surface during periods of growth. As a breeder, one must always know not only the virtues of the dog we wish to breed, but most importantly, we must also know their faults. We must breed for the whole dog, trying to find a mate that excels where our dog may be faulty, hoping to correct the faulty parts in the next generation. Again, we must look at the dog as a whole. We must know the traits essential to breed type and understand where we can “give” a little without losing breed character.

The feet of any breed serve as the foundation upon which the entire dog is “built.” Just as a contractor would never try to construct a building upon a faulty foundation, we should pay attention to the correct foot for our breed. A faulty foundation will eventually fail; if it does, the entire building is in danger of collapse. As breeders, we should pay close attention to breeding for the correct foot for our breed, as this is the foundation upon which our breeds stand.

(courtesy Showsight Magazine)